Running an LLM Locally

I spent a portion of today following Cody Wabiszewski’s guide on how to download and run the Dolphin Llama 3 model. His directions are quite good, but they miss a few things, especially when it comes to setting things up on a Mac. So for those Mac users who want expand the scope of running an LLM locally beyond Apple Intelligence, I suggest the following:

-

Head over to the Ollama website to download one of the available models. Wabiszewski recommends

dolphin-llama3and that’s what I went with. -

You start with the Ollama.app. (I’m not crazy about this, but I wanted the friendliest possible way of doing this because I wanted to make this process reproducible for others … a notion that is completely contradicted by the next step …

-

Once the Ollama app is running, you can then use the terminal to run, in two different tabs!,

ollama serveandollama run dolphin-llama3. (The latter command downloads the dolphin-llama3 model, which is about 5GB. Complete information on the model is available on its Ollama web page.)

Now, there is a slight complication: when I downloaded the Dolphin Llama 3 model, it was not located where any of the posts I read suggested. Instead, I needed to use

locateto find the directory. (If you have not runlocatebefore, you will need to let it build its database, but that does not take long – less than 10 minutes on my M1 MacBook Air with 1TB storage.) Eventually I found it in a hidden directory in my home folder:./ollama. (I would eventually like to move that to an unhidden directory dedicated to models, but I left it there for the time being.)

- Download the AnythingLLM app, install it, and then run it. Create a workspace as directed, then click on the setting gear and then the Chat Settings. If ollama serve is running, you should be able to choose it as an option. There are several clickthroughs for this.

Once this is done, you are able to run an LLM locally. (BTW, this one has no guard rails, so be careful what you ask!)

AI for Research

Now that the spring semester is wrapping up, as well as the cold that hammered me in the last half of the last week of classes, I am turning my attention to the many, many, many uses of AI. I have not explored this space for a while, and while I knew that that there had been an explosion in the commercial space, I was not aware of the growth of the space of AI in support of research.

I am currently reviewing:

- Sapien by AcademicID whose chief claim rests upon “Messages [being] backed by actual research, significantly reducing the risk of hallucination.”

- SciSpace seems more focused on an interactive query structure where the AI asks you to narrow your focus more.

- Finally, there is NotebookLM which has already been discussed quite a bit, but I am only just now catching up to that discussion.

Global Souths Faculty Roundtable Notes

I was asked to be a part of a faculty roundtable for this year’s Global Souths Conference, a conference hosted by graduate students in UL-Lafayette’s Department of English. This year’s effort was very well done, and I look forward to seeing what they do next year. Here are the questions they gave us in advance that might be discussed (in italics) along with my initial written responses, some of which I said during the roundtable and much of which I did not. (It was a lot of people and not a lot of time.)

How can scholars, educators, and practitioners work collaboratively to address the challenges facing Global Souths communities? What kinds of interdisciplinary approaches do you find promising?

The largest problem facing Global Souths communities is an economic world order where capital and, to some degree information, flow freely but people cannot. (In those places where immigration was policies were developed ostensibly to undo this problem, we have seen disastrous outcomes when nativism emerged and brought about things like Brexit, the closing of borders in Europe, and the election of the current U.S. president.)

I am not an economist, nor a sociologist, so I can make no contribution to the study of capital and people flows, but I can contribute to information flows. The work that excites me the most right now ranges from micro-scale studies of the intertwined emergence rise of colonialist and orientalist discourses, such as we heard about this morning from Yazdan Mahmoud to macro-scale studies that track conspiracy theories and how they transit social networks, localizing as they do so.

In the face of re-emergence of colonialism as we move away from what historian Sarah Paine has described as the maritime-mercantile order back to the imperial-zero-sum order, I fear that the role of the humanities scholar is primarily to document (and analyze) both the mechanisms of power as well as its machinations it works upon its victims. What we can hope for, I think, is those moments where we can protect or save someone from greater harm—but, make no mistake, harm will be done to many, if not all.

In what ways do you see the Global Souths as a conceptual framework rather than a geographic location, and how does this shape your scholarly or pedagogical approach?

The original goal of folklore studies, in conjunction with its cousin anthropology, has always been to find wisdom and beauty in the everyday existence of all the people who don’t normally make it into history. The field has made mistakes, often not crediting individuals who stood in for a larger group (a kind of hidden iconography) and because it often deals with actual people living actual lives in the current moment, it has done damage. It has also contributed real value to the academy and local communities.

I don’t know that I use Global Souths as a conceptual framework for scholarship and pedagogy so much as a way to survive institutionally: I’m a field research oriented folklorist in a department overwhelmingly focused on books and adjacent literary concerns. Majoritarian rule is real for me, and it impacts the evaluation of my work, my ability to win funding, and the seriousness, or lack thereof, with which my approach is taken. Intellectual classism is real.

What contemporary crises—whether political, economic, environmental, or cultural—do you see as defining the Global Souths today? How do these crises intersect with your own area of research?

See my response to the first question for the “nature of the problem.” As to how these things intersect, sometimes in a devastating way. When the 2005 hurricanes hit, I was halfway through a book on gumbo whose subtext was how Africanized so much of all Louisiana folk cultures are. Within a month, half the people I hoped to interview were uprooted, displaced, and relocated in ways that made them difficult to find again.

How can universities better support research and teaching on the Global Souths? What institutional challenges exist in foregrounding these perspectives in curricula? Colonialism has left a lasting mark on the Global Souths. How can scholars avoid colonial research practices in their work? How do colonial legacies continue to shape education?

We can stop doing things that replicate the very structures that reinforce colonialism and capitalism, like venerating celebrity academics and authors or engaging in intellectual classism. And, for goodness sake, stop imagining that the answer we know is either the only answer or the better answer. The whole point of folklore studies, of anthropology, and of decolonization in general was to argue that there is no one answer, that we all must live with partial answers because each of us is always already a partial self, and nothing capitalism or colonialism has to offer is going to fix that part of being human. (Well, to be clear, it works for the capitalist and the colonialist, but it depends upon a one-to-many ratio to work.)

2024-25 Holidays

With a number of Jewish holidays coming up, I thought it would be useful to look up other holidays which might also affect students ability to work. (In some cases they may be prohibited from working, and in others it may simply be that working is difficult.)

| Holiday | Date |

|---|---|

| Rosh Hashanah | Oct 2-4 |

| Yom Kippur | Oct 11-12 |

| Sukkot | Oct 16-23 |

| Christmas | Dec 25 |

| Chanukah | Dec 25-Jan 2 |

| Ramadan | Feb 28-Mar 30 |

| Mardi Gras | Mar 4 |

| Lent | Mar 5 - Apr 17 |

| Eid al-Fitr | Mar 30 |

| Passover | Apr 12-20 |

| Easter | Apr 20 |

Folklore Podcasts

Someone recently asked about folklore podcasts. Following my folkloristic ideals, as well as allowing for the fact that I can only carry so many podcasts on my listening list, I outsourced the problem to fellow folklorists. (Some may assume that this was a function of laziness, but I can assure you that, yawn, what was the question?)

Here is the list the emerged:

- Digital Folklore focuses on how thinking about digital culture through the lens of folklore studies forces us to expand the scope of both, culture and its study. It’s presented in a narrative format which can get a bit wild at times.

- Folkwise shares the importance of folklore by drawing attention to the folklore happening around us every day through digital media.

- The Fairy Tellers podcast explores what myths, legends, folklore, fables, and fairy tales have to say about cultures then and now.

- The Appalachian Folklore Podcast describes itself a “wild hike through the history and migration of the folk culture, stories, traditions, and haints hidden in hills and hollers of Appalachia.”

- It looks like RadioLab did a 12-part series on Dolly Parton that one person said was worth a listen.

- Morbid Curiosity, a history program, got high marks from one of the respondents. It describes itself as being about everything from serial killers to ghosts, ancient remains, and obscure medical conditions.

If you know of other podcasts that should be listed here, please let me know so I can update it.

Institutional Repository circa 2010

Back around 2008 I became interested in establishing an institutional repository for the university where I worked. By 2010, having spoken to a wide variety of stakeholders both within and without the university, I had a pretty good draft of what I thought was possible. It’s been passed around ever since, but we never got a repository.

And here’s the opening paragraphs:

The modern research and teaching university must emphasize that it both creates knowledge that it disseminates directly through diverse channels and that it teaches others how to create knowledge. An institutional repository is foundational in any effort to highlight the university’s centrality in knowledge creation. The institutional repository is where we collect the raw materials that drive research, publish analysis and results, and open the institutional doors to higher education’s many publics.

In the last year, a variety of developments have greatly increased the interest in establishing frameworks for securing data and making it available in a highly configurable fashion. As various units became aware that there was a common interest, it became clear that the best way forward was to arrive at a common set of requirements that would lead to a widely-available resource that would suit the greatest number of users.

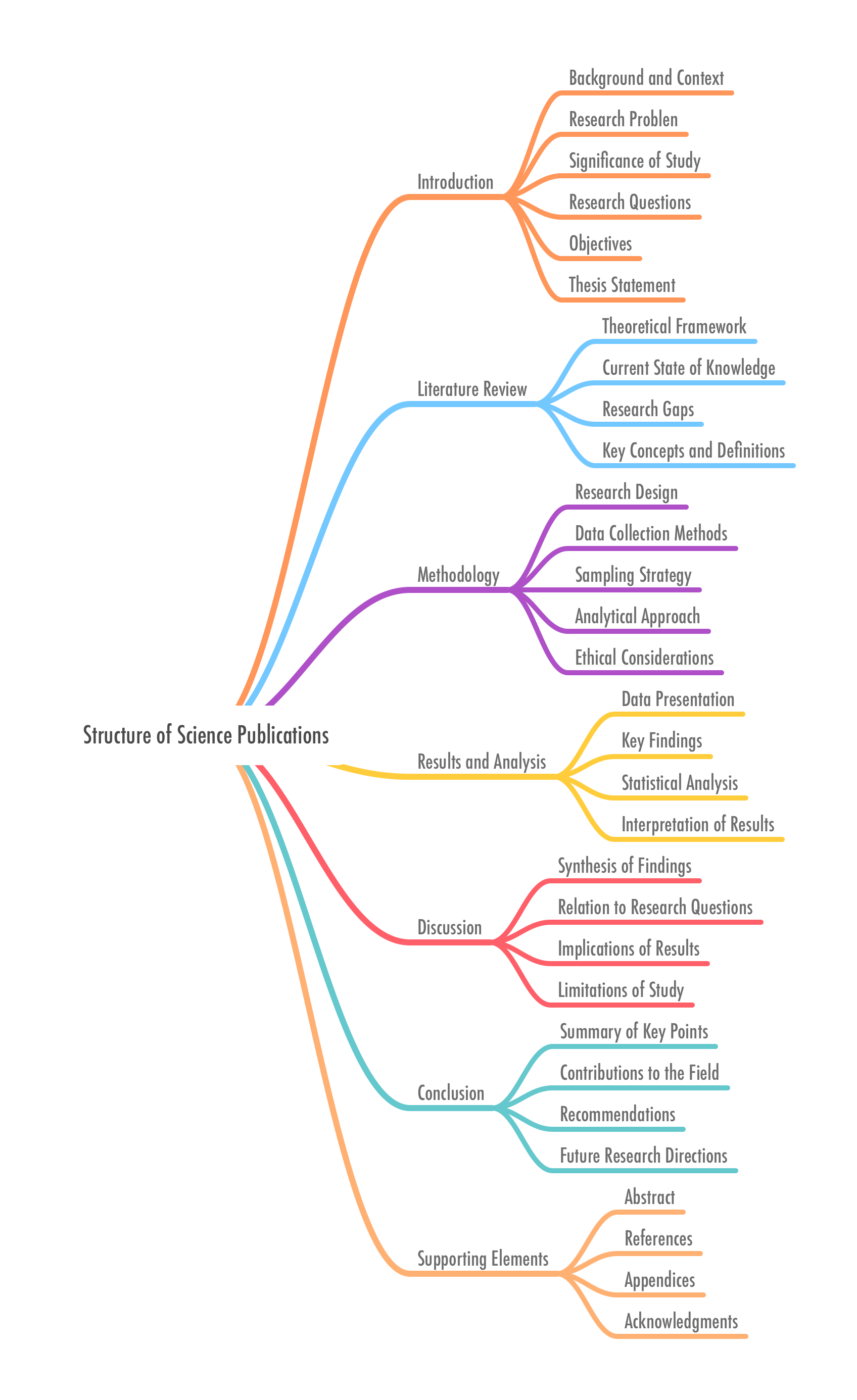

Structure of Scientific Publications

I have over the past two decades teaching in university settings regularly been called upon to teach either a specialized research methods for folklore studies or one for all the domains represented in an English department, from the very science-oriented field of linguistics to the belletristic domains of creative writing (sigh) and some of literary studies. I also regularly teach undergraduate courses, and graduate courses, that feature a research project whose end goal is a research paper aka scholarly essay or article aka term paper.

While I myself do not find the rather regimented nature of science writing to be the kind of writing I wish to do in all my essays, I have found it useful to master as a process to getting good results. That is, if you do all these things, then you have some assurance that you have done competent work. (Its worth or merit or utility will have to be decided by the field into which it is cast, like bread upon a pond surface, or perhaps it’s a lake, depending on the size of the field.)

For my students coming here for the visualization of the structure, the diagram is below. The OPML file that goes with it is also available and can be opened in most modern word processors. (I know Word will open it.) Before anyone splutters, obviously how much of this structure you realize depends on the nature and scope of your project. This is an idealized structure. Consider it a guide and not a specification.

Fall 2024 Courses

Here are the courses I am teaching this fall. The 432 is a regular feature now in our folklore course offerings and I have taught it with a focus on legends and information cascades for a few years now. The 370 is a new course, and I have to say I am looking forward to teaching a course with a non-folklore focus. I don’t get to do this often, and I am excited to see what students bring to the table.

ENGL 370. Interactive Fiction & Narrative Games. Branching narratives, interactive fiction, text adventures, CYOA all describe a form of entertainment—be it literary, performed in a group, or in a video game—in which a reader is given choices and their choices determine the nature and outcome of the story. This course explores the history of narrative games, from collaborative storytelling in oral cultures to the robust open-world games to cinematic universes in which multiple storylines exist (and sometimes interact). Course inputs include reading, viewing, and playing. Course outputs include analytical explorations of forms and mechanisms and the development of fictions of your own.

ENGL 432. American Folklore. The subtitle of this course is “Legends, Conspiracy Theories, Cryptids, Oh My!” This course seeks to explore the world in which all of us are already immersed, an online sea of information and misinformation. What are the impulses behind these flows, and what are their diverse functions. From the moment that humans became capable of re-presenting reality, we were engaged in various forms of fiction. Some forms are obviously meant for entertainment, like tales and jokes, and other forms are meant to inform and guide us, like myths and histories. In-between are the stories we tell, the information we pass along, and the arguments we make in which we conjecture about the nature of reality. Individuals interested in this course should be aware that there is as much darkness as light in what we consider and should be prepared to handle topics objectively.

A Star to Steer By

This semester I am teaching a class on Project Management in Humanities Scholarship. I have seen enough graduate students stumble when shifting from the managed research environment of course papers to the unmanaged research environment of the thesis or dissertation, that I thought it would be useful to try out some of the things we know about how best to manage projects in general as well as offer what I have learned along the way. The admixture of experts agree this works and this works for me I hope opens up a space in which participants can find themselves with a menu of options from which they feel free to choose and try. Keep doing what works. Stop doing what doesn’t.

We are a month into our journey together and almost everyone has finally acceded to the course’s manta of doing something is better than doing nothing (because the feeling of having gotten anything done can be harnessed to build momentum to get something more important done), but there are a few participants who are still frozen at the entry door to the workshop where each of us, artisan-like, is banging on something or other.

All of them have interesting ideas, but some are struggling with focus. I think this is where the social sciences enjoy an advantage. They have an entire discourse, which is thus woven into their courses and their everyday work lives, focused on having a research question. What that conventionally means is that you start with a theory (or model) of how something works; you develop a hypothesis about how that theory applies to your data (or some data you have yet to collect because science); and then you get your results in which your hypothesis was accurate to a greater or lesser degree.

Two things here: the sciences have the null hypothesis, which means they are (at least theoretically) open to failure.1 The sciences also have degrees of accuracy. Wouldn’t it be nice if we could say things like “this largely explains that” or “this offers a limited explanation of that” in the humanities? Humanities scholars would feel less stuck because they would be less anxious about “getting it right.” We all deserve the right to be wrong, to fail, and we also deserve the right to be sorta right and/or mostly wrong. Science and scholarship are meant to be collaborative frameworks in which each of us nudges understanding just that wee bit further. (We’re all comfortable with the idea that human understanding of, well anything, will never be complete, right? The fun part is the not knowing part.)

The null hypothesis works very clearly when you are working within a deductive framework but it is less clear when you are working in an inductive fashion. Inductive research usually involves you starting with some data that you find interesting, perhaps in ways that you can’t articulate and your “research question” really amounts to “why do I find this interesting?” Which you then have to translate/transform into “why should someone else find this interesting?” Henry Glassie once explained this as the difference between having a theory and needing to data to prove it, refine it, extend it and having data and needing to explain it.

There is also a middle ground which might be called the iterative method, wherein you cycle between a theory or model, collecting data, and analyzing that data. Each moment in the cycle helps to refine the others: spending time with the data gives you insight into its patterns (behaviors, trends) which leads you to look into research that explores those patterns, trends, behaviors. Those theories or models then let you see new patterns in your texts that you had not seen before, or, perhaps, make you realize that, given your interest in this pattern, maybe you need different texts (data) to explore that idea.

I see a lot of scholars, junior and senior, stuck in the middle of this iterative method without realizing it and don’t know which moment to engage first. What should they read … first? (I have seen the panic in their faces.) What I tell participants in this workshop is that it doesn’t matter. They can start anywhere, but, and this is important, start. No one cares whether you start reading a novel (and taking notes) or reading an essay in PMLA (and taking notes). 99% of managing a project as an independent researcher is just doing something and not letting yourself feel like you don’t know where to start. Just start.

Will it be the out come be the project they initially imagined? Probably not. But let’s be honest, that perfect project they initially imagined lived entirely in their heads—as it does for all of us. It was untroubled by anything like work. (That’s what makes it ideal!) It was not complicated by having to determine where we might publish the outcome, who might be interested, to what domain you might contribute. It was also unavailable to anyone else, inaccessible to anyone else, and probably incomprehensible to anyone else. As messy and subpar as the things we do in the hours we have are, in comparison to that initial dream, they are at least accessible to others, who will probably find them interesting and/or useful.

To be clear, I usually press workshop participants and students to start with data collection / compilation (and not with a theory). Mostly that’s because I am a folklorist (and some time data scientist) and I feel at my most driven when a real work phenomena demands that I understand it. To a lesser extent, as comfortable as I am with my own theoretical background, I find the current explosion in all kinds of theories a bit overwhelming. I prefer to let the data tell me what data I need to go learn, else I might end up going down the rabbit hole of great explanations and never get anything done!

-

The sciences are currently undergoing a pretty severe re-consideration of the “right to be wrong.” With the cuts in funding to so many universities — because, hey, the boomers got their almost free ride and shouldn’t have to pay for you — the American academy has shrunk, creating greater competition for the jobs that remain, which has meant that scientists often feel like they can’t fail. Failure must be an option when it comes to science, and scholarship. When it isn’t, we end up with data that has been, perhaps purposefully or perhaps unconsciously, miscontrued because the results need to be X. ↩

Test File

This is for the text analytics class: here is the file you are looking for.

To see all posts, see the archive.

<!– or search for what you seek:

–>