America in Legends Online and Off

ENGL 432 / HLG 320 / Tuesdays & Thursdays 09:30 – 10:45

Pr. John Laudun / HLG 356 / W 09:00 – 11:00 & by appt / laudun@louisiana.edu

Course Description

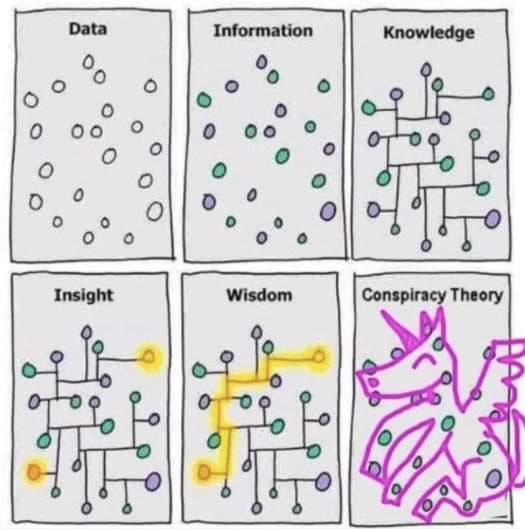

The social transmission of knowledge is central to culture and to science, but the transmission process pays little heed to its contents, often placing more value on who shares as opposed to what is shared. The study of legends takes us increasingly online, but spillage from one arena to another is common, since social networks often bridge the gaps. America in Legends Online and Off introduces participants to the study of vernacular cultures. As an advanced course for undergraduates and a foundational course for graduate students, it attempts to address materials and dynamics in terms of rhetorical effectiveness, literary/generic structure, and cultural history. The theory used in this course is a mixture of folklore studies, information science, cultural studies, and network studies. The objects of study are those forms of cultural expression that pass through offline and online social networks.

The goal of this course is to examine those materials as texts in and of themselves and to understand the sources, both structural and referential, upon which they draw. Social media is broadly imagined here: the course highlights that all media, first, have always been social, and that, second, the social world has always been mediated. Because of the personal nature of much of social media, participants in this course will need to have an open mind about the nature of meaning, and, just as importantly, about the varieties of human experience and perception. Some of the material in this course reveals the anxieties and fears, the prejudices and blindnesses, that humans too often carry with them and rarely communicate directly, instead embedding them in stories and assertions that manifest what are often tangled knots of things thought and/or felt. In some cases, the knots are not pretty.

Course Requirements

For matters of daily comportment and responsibility, please see The Essentials.

Texts

A great deal of the readings are scholarly in nature and will be available either as links to JSTOR and Project Muse or through Teams, either as PDFs or as links to sites. In addition to the on-line materials, there is at least one book required for this course:

Shifman, Limor. 2014. Memes in Digital Culture. MIT Press.

Please arrange to purchase the book through your preferred vendor. (Please make sure you have a complete version of the book and can access it readily.) Depending upon the make-up of the class and emergent interests, there may be a second book to purchase, so be sure to set aside a portion of your budget for that expense, in addition to the cost of printing other materials as needed. I strongly recommend spending the little bit of money to print PDFs. Print them, mark on them, doodle on them, highlight them. Studies have shown that hand-written notes are better for intellectual development. I suspect the same will eventually be discovered for reading.

Assignments

The assignment schedule for this course is simple:

- Participation (30%). Half the participation grade is dependent upon your being in class and being an active part of discussions through active listening and thoughtful contributions. The other half of the participation grade is a function of a collection of small assignments: taking responsibility for a discussion, completion of in-class writing assignment, etc.

- Mid-term essay/exam (20%). At the mid-term, this course asks that you write an essay synthesizing your understanding of the study of vernacular culture based on the materials we have read and the discussions we have had. The essay must be well–structured and sourced. (Bonus points are awarded for quoting a fellow participant.)

- Course Project (50%). The course project requires independent enterprise on the part of course participants, who are free to choose from a wide variety of topics, so long as they can make a case to me both in the intial proposal and in the paper itself that it fits within the scope of the course. The wide possible scope is on purpose, but negotiating the parameters of the project with the instructor is required. For more, see the course project specifications page. Note well: half the credit for the project is for the drafting stage, which requires participants to turn in materials on time and completed.

Infrastructure

Students in this course will receive and submit assignments using either markdown-formatted plain text or LaTeX through GitHub. GitHub accounts are free, and will continue to be so after you leave university, unlike Microsoft 365. Moreover, version control is a central focus of most professional endeavors, and getting a better grasp of it, even if you are forced to go back to Track Changes in Word, is an essential part of your education in this course.

Institutional Necessities

One day, the University will create a central resource that collects stuff like this, but until then, they ask faculty to include things like this:

Emergency Evacuation Procedures

A map of this floor is posted near the elevator marking the evacuation route and “Designated Rescue Area.” Students who need assistance should identify themselves to the instructor.

Accessibility Services, Disability Services, & Other Helpful People

The university maintains a wide variety of services and centers designed to help students who have either ongoing or emergent needs. Please do not hesitate to contact Academic Support Services, and don’t be embarrassed to talk to me.

Schedule

The weeks below suggest that this course follows a fixed, calendrical schedule; it is labeled an agenda for a good reason: sometimes discussions move more quickly or more slowly and schedules change. If you miss class, reach out to one of your fellow participants to ascertain where we are in the agenda.

In most cases, the direct link to an article or other kind of resource is posted below. In a number of instances, the direct link is to JSTOR, since that is where a number of folklore studies journals are archived. Please see the note on accessing materials for more information on successfully accessing databases and data repositories. For those materials not linked, they will be found in Teams: Files > readings.

Foundations

Week 1: Essentials. On the first day of the course, after we review the syllabus, we lay out some foundational concepts in folklore studies. For the following class, we read Jakobson and Bogatyrev’s short essay and then consider artifacts and products in your own life: are they literary or folkloric? List at least five examples of each and determine if there is something more you can say about either the categories or the boundaries between the categories. That is your response should include two lists and then some synthesis.

Jakobson, Roman, and Petr Bogatyrev. 1971. On the Boundary Between Studies of Folklore and Literature. In Readings in Russian Poetics: Formalist and Structuralist Views, 91–93. Edited by Ladislav Matejka and Krystyna Pomorska. Michigan Slavic Productions.

Week 2: Functions. Read Bascom’s “Four Functions of Folklore.” Make sure you understand both contexts and functions. Apply Bascom’s heuristic to one item from your list from the previous assignment. Afterwards, read Burke’s “Literature as Equipment for Living.” In that essay, Burke argues, first, that proverbs aren’t simply things we say, but rather we do things with them. One of the things they do is name situations, giving us a way to deal with them. He then argues that other genres of discourse do something similar. Novels, for example, name situations. Following Burke, you could argue that pop songs name situations, or, as we might put it, “speak for us.” As you read Burke, find at least one situation that has multiple proverbs associated with it and list the proverbs, noting how the different proverbs offer different ways of understanding and treating the situation. As you read about the second section, list a novel and/or song(s) that speak for you. You might find that certain songs are associated with certain moments in your life. How and why did that happen?

Bascom, William. 1954. Four Functions of Folklore. Journal of American Folklore 67 (266): 333-349. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/536411.

Burke, Kenneth. 1941. Literature as Equipment for Living. In The Philosophy of Literary Form, 293-304. University of California Press.

Week 3: Conduits & Cascades. Beyond the core concepts of folklore studies, there are some particular concepts, and terms, we need to include within our analytical toolkit in order to understand how online “communities” work. (The quotation marks indicate that we need to think about how we use terms: what it naturalizes and what it does not.)

Be forewarned: both the readings for this week are long. For PhD students, this will be an easier pace; for new MA students, this is going to feel like a bit of uphill; for undergraduate students, this is going to feel like one of those trips that your parents dragged you along and you got tired and just wanted to sit down so you found that one place in the middle of a clothing rack which was calm and peaceful and your parents freaked out when they couldn’t find you but what did they expect dragging you around like that?

None of this material is familiar to you, I know, and so part of what you are learning is how to read as best you. For most, you might be well suited, first, to print the essay, then flip through its pages, skimming the first sentence or two of each paragraph just to get a sense of the kind of language being used and maybe just a bit of a sense of how the argument is being made: how the analysis is conducted and how the synthesis is worked.

That is, read as both a student of the content but also a student of the form: each of you will be tasked with coming up with your own research project and when you ask me how you should proceed I am going to point you right here, to what you have read. How do these scholars and scientists go about their work?

Activity for you to try: List the groups of which you are a part and then, using a network graph, try to chart the usual flow of information through those groups. What role do you play? Are you the bridge between groups or are there a number of people who overlap a group? How does that affect the flow of information.) Your assignment is to report on your findings and to submit a network graph of at least three groups of which you are a part. (Please just label everyone not you with their initials: we are not engaged in social graph surveillance in this course.)

Dégh, Linda, and Endre Vázsonyi. 1975. The Hypothesis of Multi-Conduit Transmission in Folklore. In Folklore. Performance and Communication, edited by Dan Ben-Amos, and Kenneth Goldstein, 207–55. Den Haag: Mouton.

Bikhchandani, Sushil, David Hirshleifer, and Ivo Welch. 1992. A Theory of Fads, Fashion, Custom, and Cultural Change as Informational Cascades. Journal of Political Economy 100 (5): 992-1026. 10.2307/2138632.

Nota bene: I will, when I can, provide guidance on some of the essays we are reading. While this is a senior level class for undergraduate students and an entry-level class for graduate students, which means you expect to read scholarship!, I recognize that this course takes many of you pretty far afield of your comfort zone. With that in mind, when reading the essay by Bikchandani, Hirshleifer, and Welch, I have the following advice:

- Skip the math. (This means you can ignore the appendix, which starts on page 27—so, if you’re printing the essay, start on page 2 and go to 27. Save some paper; save a tree.)

- In general, if you can’t make sense of it when you first encounter it, don’t stop. Keep reading. The next sentence or paragraph or page may be what you need to read for things to click in place. (If you get to the end and nothing has clicked, you’re just going to have to start over.)

- There are some interesting “cases” towards the end of the essay, so during the drier parts, know that there are some digestible bits coming up.

Unintended Consequences.

Ellis, Bill. 2015. “What Bronies See When They Brohoof: Queering Animation on the Dark and Evil Internet.” Journal of American Folklore 128(509): 298–314. https://doi.org/10.5406/jamerfolk.128.509.0298.

Blank’s binders + student paper.

Shifman, Limor. 2014. Memes in Digital Culture. MIT Press.

Scary Things Off and On the Internet.

Ellis, Bill. 1989. “Death By Folklore: Ostension, Contemporary Legend, and Murder.” Western Folklore 48 (3): 201–20. DOI: 10.2307/1499739.

Laudun, John. 2020. The Clown Legend Cascade of 2016. In Folklore and Social Media, edited by Andrew Peck and Trevor J. Blank, 188–208. University Press of Colorado. 10.2703/j.ctv19fvx6q.14.

Slender Man. We will be reading articles found in a special issue of the journal Contemporary Legend (URL). As we move closer and closer to that moment in which you embark upon your own research project, I will taper down my contribution to the class discussion in order to ramp up each and every one of you to find your voice. In particular, as you read the articles about Slender Man, you will want to take notes about what this phenomenon reminds you of. It doesn’t have to be something on which you are an expert or something you want to research, just something that you find interesting and would like some help thinking through. The crux of this is to understand the importance of thinking with others.

Conspiracy Theories. Read O’Connor and Weatherall’s “Why We Trust Lies.” Neither of them are folklorists: what are their backgrounds and how do you think that affects their understanding of information, of learning, and of trust?

O’Connor, Cailin, and James Owen Weatherall. 2019. Why We Trust Lies: The Most Effective Misinformation Starts with Seeds of Truth. Scientific American September: 54-61.

Tangherlini, Timothy, Vwani Roychowdhury, and Peter Broadwell. 2020. Bridges, Sex Slaves, Tweets, and Guns: A Multi-Domain Model of Conspiracy Theory. In Folklore and Social Media, eds. Andrew Peck, and Trevor Blank, 39-65. University Press of Colorado, Utah State University Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctv19fvx6q.