Honors Freshman English

Course Logistics

Meetings: MW(F) 11:00-11:50, HLG 122.

Instructor: Pr. John Laudun

Office & Hours: HLG 356. MW 9:00 – 10:30, 2:30-3:00, and Tuesday mornings by appointment. 482-5493. laudun@louisiana.edu.

Course Description

My goals for this course are simple: first, to de-mystify reading as a process into a series of discreet activities so that students can understand how texts work: through content, through structure, and through intertextuality; second to have students practice various forms of writing, focusing especially on those forms that help you practice analysis and argumentation. Such writing assignments include, but are not limited to, summaries, outlines, analytical responses, and, of course, the synthetic essay.

Course Materials

Depending upon the semester, there will be books listed below, but the first thing you need to do is to log onto the course’s Moodle site. (Please come to class before purchasing any books for this class. Sometimes plan change between the time the syllabus is constructed and the time at which a final plan is developed.) Over the years I have developed a number of custom versions of common texts in order to make it easier for you not only to engage in various kinds of reading practices and analyses but also to make sure there are common page numbers to enable better discussions. You will be responsible for printing these materials and having them in class, marked up, and ready to discuss. Reading from devices is prohibited and only reveals you have not read the syllabus clearly.

The books you need to buy are:

Dick, Philip K. 1970. A Maze of Death. Vintage. (We are going to use the 2013 reprint.)

Order the books from your favorite bookseller, the university bookstore or Amazon.

There are also a number of texts which are not scribal in nature. That is, this course also takes advantage of various video and audio presentations. Many of these are available in forms that require only a computer and internet connection of modest means: that is, you must have access to a computer that can accept video and audio streams. Some of the materials are copyrighted and require that you own them or you have access to them through a subscription service. You will need to arrange access to physical copies of these texts or to subscribe to services that provide you access to them. (The services you need are noted with the texts below, and you should add those costs to the total costs for this course. No exceptions.)

Sadly, both the mainstay word processing applications, Microsoft Word and Apple Pages, are terrible at collaboration, review, and revision. This course uses Google Docs for major writing assignments: please make sure to familiarize yourself with its features and functions at your earliest convenience – announcing you do not have a Google Drive account or do not how to use it when an assignment is due means you haven’t read the syllabus. I will only interact with drafts either in this format or in plain text using either Markdown or LaTeX via GitHub. (I will also provide you with a standard file-naming scheme for each document I ask you to submit: use it.)

Finally, put away the spiral-bound notebooks, especially the multi-subject ones. Get yourself a notepad and a collection of file folders. More will be explained in class, but you should start by reading this note.

Course Requirements

The goal of the course is to help students learn how to read more closely and with an eye to possible outcomes. Much of the grading of the course then focuses on written products as either documentation of reading practice or as various kinds of outcomes. Everything is in words: sometimes presented orally, and even dramatically, and sometimes scribed.

- Small writing activities appear constantly throughout this course. They are typically graded for competence and then for excellence. They are worth a total of 30 percent.

- Participation in class activities and discussions is not simply a matter of being bodily present but of engaging actively, with excitement for the possibilities and respect for others’ efforts. The 20 percent here should not be assumed but earned.

COVID Update: No final exam will be given, unless requested by the student one week in advance. The course project will be worth 50 percent of the final grade.

- The big writing project in this course, worth 30 percent, is graded as a portfolio that may include a proposal, a research report, drafts of various parts of the essay, as well as the essay itself. The project is itself divided up across a number of activities: first body paragraph, second and third body paragraphs, first draft, second draft, and final draft. (Yes, the process really is that involved.) Drafting is so important that it is worth half the grade: drafts must be submitted on time to count.

Course Dynamics

First, all students should read Rob Jenkins’ essay on “Defining the Relationship.” Jenkins is also a professor of English at a regional state university in the south. His approach is similar to the one in this course.

Discussion, completion of assignments, and participation in course activities are an important part of how I structure a course. I prefer not to lecture from any given book so that I can add to our discussion and not repeat material found elsewhere – if repetition is important to you, then this may not be the course for you. It should also be noted that course discussions, by design, are wide-ranging. I regard class meetings in the same light as most professionals: they are necessary and you must take notes no matter who is talking. (And it goes without saying that you deserve everyone else’s respect, and they deserve yours.) An important part of participation is being in the room on time: every student is spotted three unexcused absences. Thereafter, each absence will remove up to ten percent of the final grade: this is in addition to null values entered for participation and missed assignments.

Note-taking is your responsibility, as is keeping up with what is happening or happened in class on a given day or what is due in class following your absence. (Not handing in an assignment because you didn’t know about it because you missed class and did not contact one of your classmates still counts as not handing in the assignment.) Please write down the name and contact information of at least one other member of this class.

The university maintains a strict absence policy. If an absence is at all foreseeable, especially if it falls on a due date, you should let me know as much in advance as you can in order to find a solution. The same goes for arriving late or departing early. If you are more than five minutes late, you will not be admitted to class – unless you have a very good narrative and can perform it with a zeal glimpsed only in performances by Cirque du Soleil or Frank Sinatra.

Turn off all sources of distraction before coming into class. Cell phones must be set to silent and put away, unless you are expecting an emergency telephone call, in which case you should talk to me before class starts and sit near an exit so that you can excuse yourself and step outside to take the telephone call.

Let me state this again: no cell phones. [Simon Sinek has a good account][] of how cell phones satisfy us and, at the same time, keep us from the kinds of actions that lead to long-term things like relationships and satisfaction.

All of you have a copy of the Code of Student Ethics. If you do not, please get one. All forms of academic dishonesty — e.g., cheating on exams, plagiarism in papers — will be taken very seriously in this class. At minimum, you will receive an F on the assignment, but there is also the possibility of receiving an F in the course or being dismissed from the university. I personally do not want to consider the possibility of turning over the design of a bridge that my family will cross to an engineer who cheats nor the diagnosis of a medical condition to a doctor who cheats. Many of you are from Louisiana and remain in Louisiana and thus will remain a part of my world: being surrounded by individuals whom I trust and admire is important to me. Please give me every opportunity to do so.

Institutional Necessities

One day, the University will create a central resource that collects stuff like this, but until then, they ask faculty to include things like this:

Emergency Evacuation Procedures

A map of this floor is posted near the elevator marking the evacuation route and “Designated Rescue Area.” Students who need assistance should identify themselves to the instructor.

Accessibility Services, Disability Services, & Other Helpful People

The university maintains a wide variety of services and centers designed to help students who have either ongoing or emergent needs. Please don’t hesitate to contact any of these folks, http://louisiana.edu/academics/academic-support-services, and don’t be embarrassed to talk to me.

Your Secret Identity

In some semesters, each student is assigned a “secret identity.” The assignment is purely random: it consists of pairing your name with a some kind of token. Do not share your secret identity with anyone and do not ask anyone to share his/her secret identity with you. It is permissible, however, to design a game within which secret identities are used and thus disclosed. Be prepared for players to balk at anything that requires direct disclosure: your game must be compelling enough that revelation of their secret identity is something they are willing to “pay” in order to play. There is some reward for maintaining your secret identity throughout the semester. (Just some, not a lot.)

Course Schedule

This course, like all university courses, operates within the larger framework of the university’s schedule, including various breaks and exam periods. Because each class is different, the schedule of assignments is not tied to any particular date but tied to a given sequence of events:

Dangerous Games

The first few weeks of the semester focus on the short story “The Most Dangerous Game” (1924) and various ways to break up the text and the work associated with analysis.

| Text | Link |

|---|---|

| “The Most Dangerous Game” | |

| “The Most Dangerous Game” | text |

| Wikipedia entry for story | url |

| “The Most Dangerous Game” (film) | youtube |

| Wikipedia entry for film | url |

Assignment: group development and production of an adaptation of “The Most Dangerous Game” suitable for presentation to the rest of class. Maximum run time of 10 minutes. Please be sure to follow the criteria we develop in class.

Arenas

| Text | Link |

|---|---|

| “Arena” | pdf / text (See Stockwell 2002 for more on storyworlds and inheritance.) |

| Star Trek: The Origianl Series: “Arena” | Netflix / Amazon / pdf / text |

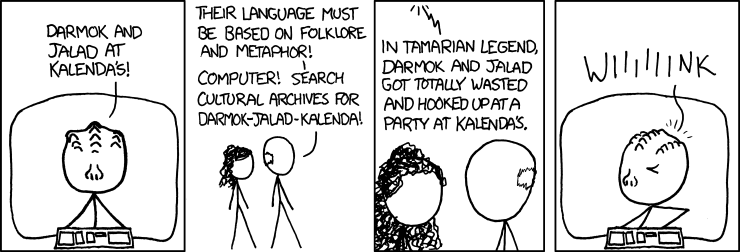

| Star Trek: The Next Generation: “Darmok” | Netflix / Amazon / pdf / text |

The Meat in the Machine

The rest of the semester will be occupied with a consideration of what it means for so much of ourselves to be caught up in a collection of files that pass from one machine to another most often in ways invisible to us. Currently, the following texts are included in our course. They are all available in a folder labeled Texts on the course Moodle site and can be downloaded individually or in bulk.

| Date | Text |

|---|---|

| 1909 | E. M. Forster, “The Machine Stops” |

| 1938 | Murray del Rey, “Helen O’Loy” (See note below.) |

| 1945 | Isaac Asimov, “Escape!” |

| 1946 | Murray Leinster, “A Logic Named Joe” |

| 1950 | Alan Turing, “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” |

| 1954 | Frederic Brown, “Answer” |

| 1956 | Robert Silverberg, “The Macauley Circuit” |

| 1968 | Harlan Ellison, “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” |

| 1970 | Philip K. Dick, A Maze of Death |

| 1970 | Colossus: The Forbin Project (film) |

Notes

- The Forster story has seen some recent uptick in references (see: Cowles 2021).

- Many of these texts are well-known and have Wikipedia entries written about them. In addition, it should be noted that there was actually a series of computers called Colossus that were part of the British code-breaking effort during and after WW2.

- del Rey’s story veers from our topic in being a story about embodied AI, and as such we cannot escape its clear ties to tropes and texts about Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Also be sure to check out the Gendered Text Project’s mutable version. For an interesting take on the sexism in the story, check out Dominick M. Grace’s “Rereading Lester del Rey’s ‘Helen O’Loy’” (on JSTOR).

Analytical Essays

Franklin, H. Bruce. 1983. Don’t Look Where We’re Going: Visions of the Future in Science-Fiction Films, 1970-82 (“Ne cherche pas à savoir où on va”: les Visions de l’avenir dans le cinéma de SF de 1970 à 1982). Science Fiction Studies 10/1: 70-80. JSTOR.

Goldman, Steven L. 1989. Images of Technology in Popular Films: Discussion and Filmography. Science, Technology, & Human Values 14/3: 275-301. JSTOR.

Alarmist Reports & Considered Histories

- AI will eliminate 6 percent of jobs in five years, says report. What are cognitive services?

- When do the Laws of Robotics apply?

- Tech Giants Team Up To Tackle The Ethics Of Artificial Intelligence

- The first Colossus.

- Computers inventing their own language/code.

- The Verge has done a nice job over the years of keeping discussions about AI at a fairly high-level. In 2014, they offered and then again in 2019 they offered “AN AI READING LIST — FROM PRACTICAL PRIMERS TO SCI-FI SHORT STORIES”][verge2019]. https://www.theverge.com/2019/1/29/18200585/understand-ai-artificial-intelligence-reading-list-books-scifi

AI/Machines in Other Texts

| Date | Text |

|---|---|

| 1966 | Billion-Dollar Brain (book, film) |

| 1983 | WarGames (film) (Wikipedia) |

| 1999 | Smart House (Disney film) |

| 2001 | A.I. Artificial Intelligence (film) (Wikipedia) |

| 2006 | Daniel Suarez, Daemon |

| 2013 | Her (film) (Wikipedia) |

| - | The Machine (British film) |

| 2014 | Automata (film) |

The Wikipedia entry on Artificial Intelligence in Fiction is well worth your time.

Other Links

- Inverse: Inside the ‘Westworld’ Set’s Luxury Dystopian Cowboy Disneyland “The main things people want to do in Westworld is they want to kill, eat, or have sex”

- In a meta moment, there’s another course about the same topic as this one.

Algorithms

Concluding his review of Ed Finn’s What Algorithms Want, Scott Selisker notes that:

While it’s tempting to imagine algorithms as either impartial bystanders or Daemon-like monsters that might take on lives of their own, seeing them as bigger systems helps us to advocate for more just arrangements and better information. What Algorithms Want explains how we all have a stake in shaping the algorithms that have, for all intents and purposes, already taken over.

Course Paper

The final paper in this class asks you to reflect on the methodological work we have done in terms of understanding texts and the topical considerations for the term – in this case how we imagine “artificial intelligence.” Your objective is to complete by the end of the semester an essay which takes up a text, or several texts, that we did not discuss in class and examine it for its representation of how intelligences, human and artificial, relate, reflect, refract a particular concern, anxiety, question or some other topic of your choosing. The paper must be grounded in textual evidence and that evidence must be presented in a contextualized fashion and a considered sequence such that your audience is “naturally” led from your initial proposition to agreement with your thinking on the matter.

Just to be clear, the essay must be 3500 words, which does not include extensive quotations nor your works cited; it must be turned in on paper with one-inch margins, double-spaced, and in a reasonable 12-point serif type face. (If you aren’t sure on any of these parameters, especially type face, check with me. Don’t surprise me.) Your paper must be well-sourced, though I do not require any given minimum nor maximum number of sources.

Bibliography

Stockwell, Peter. 2002. Cognitive Poetics: An Introduction. Routledge. Moodle.

Turing, Alan. I. 1950. Computing Machinery and Intelligence. Mind LIX(236-October): 433–460. DOI: 10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433.